- Home

- Lisa Graff

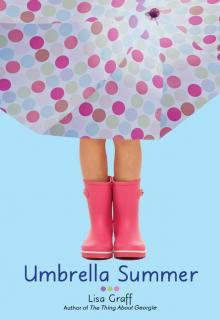

Umbrella Summer

Umbrella Summer Read online

Umbrella Summer

Lisa Graff

To Ryan

Contents

One

If you started to squeeze your brakes right in the…

Two

When I got home, I sat down on the porch…

Three

I stayed at that table the whole rest of the…

Four

I read the big green book for almost two hours,…

Five

When I woke up Sunday morning, there was a word…

Six

“Annie?” my mom called from out in the hallway.

Seven

Rebecca stayed at my house the rest of the afternoon,…

Eight

Monday morning after Mom left for work and Dad started…

Nine

While Mrs. Finch led me into her house, I kept my…

Ten

When I got home, I started reading right away, flopped…

Eleven

The next day was the Fourth of July, which meant…

Twelve

When we were finished with the singing and the official…

Thirteen

As soon as I opened the front door, Mom called…

Fourteen

I peeled off all my Band-Aids careful slow—off my arms…

Fifteen

The next morning I still had that headache, and my…

Sixteen

Lunch was SpaghettiOs from a can. I chewed extra slow,…

Seventeen

I didn’t know what was going to be in that…

Eighteen

We put the fish photo up at one end of…

Nineteen

The next afternoon Mrs. Finch opened her front door with a…

Twenty

Dad dropped me off at the Bowling Barn Friday evening,…

Twenty-One

About ten o’clock Saturday morning I strapped on all my…

Twenty-Two

That night I woke up all of a sudden, and…

Twenty-Three

The instant I woke up Sunday morning, my brain reminded…

Twenty-Four

When we got back home, there was a leaf stuck…

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books by Lisa Graff

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

one

If you started to squeeze your brakes right in the middle of heading down Maple Hill, just as you were passing old Mr. Normore’s mailbox, you could coast into the bike rack in front of Lippy’s Market without making a single tire squeak. That was the fastest way to go, and the most fun too, with the wind whistling past your ears and your stomach getting fluttery and floaty, till you thought maybe you were riding quicker than a rocket.

I didn’t do that anymore, though. Now I hopped off my bike at the top of the hill and walked it. It took five times as long but it was lots safer.

I got to the store at 7:58—that’s what it said on the clock inside. The door was still locked, and Mr. Lippowitz and his son, Tommy, were flattening cardboard boxes in the corner. Mr. L. saw me peeking through the window and held up two fingers, so I sat down on the front step and waited, trying to soak up the whole two minutes by taking off all my biking gear real slow. I slid off my elbow pads—left one first, then the right—and stacked them on the step next to me in a pile. Next came the kneepads, which I tugged off over my sneakers, and last of all I unsnapped my bike helmet. I thought about taking off the ace bandages around my ankles, too but then I decided it would take too long to put them back on when I was ready to bike home, and there was no way I was biking without them. They were important for protecting against sprains.

I took so long with my bike gear, I swear Mr. L. could’ve opened the store twice by the time I was done, but the door was still closed. I stood up and leaned back on my heels and then forward to the tippy-tips of my toes, just for something to do while I was waiting, and I scanned the bulletin board out front to see if there was anything new.

Same as usual, there were papers pinned up all over—advertisements and lost-and-founds, flyers about art lessons and people selling furniture and high school kids looking for babysitting jobs. In the top right corner there was a green one that said YARD SALE SATURDAY—106 KNICKERBOCKER LANE, and I knew that had to be the Harpers next door, because my house was 108. Some of the flyers were brand-new, and some were so old they were brown around the edges from too much sun. My dad once said that if you ever wanted to know what people were up to in Cedar Haven, California, the easiest way was to go down to Lippy’s, because then you could learn about everyone all at once.

By the time Mr. L. unlocked the door, it was 8:09, but I didn’t tell him that. “Well, if it isn’t my best customer!” he said with a grin. “How are you doing today, Annie?”

“Pretty good,” I told him. “I checked our house for black widow spiders, and there aren’t any.”

“Well.” His nostrils flared at that. “Good to know.”

There was a crash from the back room—not an emergency-sounding shatter like plates breaking, but more like a good long rattle.

“Tommy!” Mr. L. hollered over his shoulder. “What was that?”

Tommy didn’t answer.

“Sounded like a whole carton of Good & Plentys to me,” I said.

He laughed. “I better go check, huh?”

While Mr. L. checked on Tommy, I wandered around. I knew exactly what I was looking for, but I liked exploring. Lippy’s was one of my favorite places to be. Sometimes on Sundays, after Rebecca’s family got back from church, we rode our bikes down to get lunch from the warmer. Rebecca got either fried chicken or spiced potato wedges, and I always got beef taquitos. It was four for two dollars, but if Mr. L. was at the register I got a fifth one for free.

I saw right away that Mr. L. had finally stocked up the toy aisle for summer—water balloons and Super Soakers, snorkel masks and plastic sunglasses. He should’ve gotten that stuff out three weeks ago, because it was already the first day of July and I was sweating worse than a pig in a roller derby. But I guess better late than never, that’s what my mom always said. There was a pair of brown-and-pink polka-dotted flip-flops that were just my size, and I wanted them real bad, but there were more important things I needed to spend my money on.

After I finished my wandering, I went to the front, where Mr. L. was reading the newspaper behind the counter.

“Was it Good & Plentys?” I asked him. “Is that what crashed?”

He shook his head. “Junior Mints. You find something worth buying today, Annie?”

“Yup.” I slapped my purchase on the counter.

Mr. L. looked at the box and then looked back at me. His face was squinty. “Didn’t you just buy a box of Band-Aids yesterday?” he asked.

“It was Thursday,” I told him, “and I’m out already.”

I saw him looking at my arms. I had two Band-Aids on the right one, where Rebecca’s hamster had scratched me with its nails, and five on the left one, covering up spots that were either mosquito bites or poison oak, I wasn’t sure yet.

He sighed deep. He was looking at me with his eyes big and sad, and a crease between the eyebrows. It was the same look almost everyone had for me now, Miss Kimball at school, my parents’ friends, even Rebecca sometimes when she thought I couldn’t see her. Everybody on the planet practically had been looking at me the same way since February—sad and worrying, with a bit of pity mixed in at the edges. I guess that was the way people looked at you after your brother died.

I slipped three dollars across the counter toward him. “I get seventeen cents change,” I said.

Mr. L. just nodded and rang me up.

When I was outside trying to yank my kneepads back up around my knees, I noticed Tommy by the Dumpster. He was gnawing on a handful of Junior Mints.

Tommy had never really talked much, but it seemed to me he talked less than normal lately. I liked hanging out with him though, even if he was two years older, because he was the one person who never gave me that dead-brother look. I guess that’s because he’d been Jared’s best friend, so he probably had people giving him enough dead-best-friend looks to know better.

He must’ve seen me staring, because he held up the box of candy. It had a rip in the corner. “They got damaged,” he said.

I shrugged. “Can I have some?”

He shrugged back. “Guess so.”

I yanked my right kneepad up one more inch and went over to the Dumpster. Tommy shook some Junior Mints into my hand. He was eating his quick back-to-back, but I sucked on mine slow, until the chocolate melted away and all that was left was peppermint. We stood in the parking lot and chewed and sucked for a long time, just quiet. I tried to look at Tommy sideways without him noticing while I rolled a new piece of candy around on my tongue. He had blond hair that was the length my mom called “shaggy,” and it covered up his whole eyebrows. That would’ve driven me nuts, but Tommy didn’t seem to mind.

I was thinking about that when Tommy popped another Junior Mint into his mouth and said, “We were gonna go bowling this year.”

I nodded. Jared and Tommy had their birthday party together every year, since they were born only two days apart, July seventh for Tommy and the ninth for Jared. They either went to Castle Park, where they had miniature golf and video games, or else they went bowling. I liked bowling better because I always had to come, and when it came to video games I stunk worse than old asparagus.

“You still gonna go?” I asked him. I plucked another Junior Mint from my hand and let the chocolate settle onto the top of my tongue.

He shook out the last of the candy into his mouth. “Maybe. I guess.” He tossed the empty box into the Dumpster. “I don’t know.”

He was about to go back inside the store, I could tell, but for some reason I didn’t want him to leave just yet.

“Tommy?” I said.

He turned around. “Yeah?”

Then I realized I shouldn’t have said “Tommy?” with the question-mark sound in my voice, because that made it sound like I had a question to ask him, which I didn’t. So then I had to think of one. “Um, if you were writing a will, what do you think you’d put in there?”

Tommy raised an eyebrow. “A will?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Like, when someone dies and they leave you stuff.” I hadn’t been planning to talk to Tommy about wills. But I’d been thinking about them for a while, how they were good to have around for just-in-case times. If Jared had made one, I was pretty sure he would’ve given his robot collection to me, so it wouldn’t just sit shut up inside his bedroom where Mom said it should be. “What would you write?”

Tommy still had his eyebrow up. It was a look Jared sometimes used to have when he talked to me, that look that meant he couldn’t believe he was related to someone so stupid. Usually after a look like that, Jared gave me a wet willy and told me to stop being a moron, but Tommy just said, “What do you mean, what would I write?”

“Like, what sort of stuff would you give away, and to who?”

He was quiet for a while, thinking I guess, and I sucked on my last Junior Mint until it was just peppermint air.

“I don’t know,” he said at last. He shrugged when he said it. “Probably no one wants any of my stuff anyway.” He squinted at me from under his shaggy hair. “Why do you want to know?”

I tapped the Band-Aid box bulge in my front pocket. “I’ve been thinking about writing one,” I said. “But I can’t figure out who should get which things.” Like my stuffed turtle Chirpy, the one Jared gave me for my birthday three years ago, and my snow globe from Death Valley. Should I leave that stuff to my parents? Rebecca? The Goodwill box at school? It was hard to figure out.

“Okay, well”—Tommy did head for the door then—“good luck.” And I knew that meant we were done talking. I finished putting on the rest of my bike gear, checked three times to make sure my shoelaces were double-knotted, and then whacked up my kickstand.

The whole way home, with the corner of the Band-Aid box poking into my hip as I walked my bike slowly up Maple Hill, I thought about it. My will. The best thing to do would be to make one as soon as possible, because you never knew when you were going to need it, and it was best to be prepared. But the reason I was having problems was because most of the stuff I had, if I could give it to anyone, I’d want to give it to Jared.

And Jared was gone.

two

When I got home, I sat down on the porch steps to change one of my Band-Aids, because the edges were looking kind of grimy. Then I noticed some bumps on my left leg, just above the knee. There were two of them, red and itchy, and they looked like bug bites, but I checked all over to make sure there weren’t more of them, because that could mean they were chicken pox. I’d never had that one before, and there’d been a boy at the library last week who looked pretty itchy. I’d told Mom the kid seemed chicken poxy right when I saw him, but she just rolled her eyes.

Mom was always saying I shouldn’t worry so much, but I knew for a fact that she didn’t worry enough. Because last February when Jared got hit with a hockey puck playing out on Cedar Lake, Mom took him to the hospital, and the doctor said he just had chest pain from where the puck had hit him, and Mom believed it. And then two days later, Jared died. There was a problem with his heart. The doctors at the hospital said it was incredibly rare, that’s why no one had thought to check for it. But rare didn’t matter for Jared, did it?

The problem was, you couldn’t just look out for the big things—cars on the highway and stinging jellyfish and getting hit by lightning and house fires and pneumonia. Everyone knew that stuff was dangerous. But there was a lot of other dangerous stuff that most people didn’t even think to worry about. You had to watch out for everything.

I was checking underneath my sock for more red bumps when a head popped up on the other side of the hedge and scared me so bad, I lost my balance and fell right over in the grass.

“Why, hello there, Annie! Oh, I’m so sorry, dear, I didn’t mean to startle you.”

It was Mrs. Harper, our next-door neighbor, who did not normally scare the bejeebers out of me.

“That’s okay,” I told her. I stood up and patted all my bones to make sure none of them were broken. They weren’t. “I’m all right.”

“Glad to hear it,” she said.

Mrs. Harper was a fairly large lady, as big around as one and a half of most people, and she liked giving hugs. Every time she saw you, she’d squeeze you up tight into a hug and hold on to you so long that you could sing the whole “Star-Spangled Banner” before she was done. She was our troop leader for Junior Sunbirds, so every meeting the hugs could go on forever. “What are you up to over here?”

“Just checking to make sure I don’t have chicken pox,” I told her, brushing the grass off me.

“Oh.” Mrs. Harper cleared her throat then, even though I could tell it didn’t really need clearing. “I see. Well”—she cleared her throat again—“anyway, Mr. Harper and I are having a yard sale today. Would you like to come over and take a look? We have some of the kids’ old toys and things.”

I peered over the hedge into their yard, and sure enough, there was Mr. Harper, arranging a pile of old mugs on a fold-out table. There were tables all over the yard, actually, but I couldn’t tell what was on most of them. A couple of people from our neighborhood were already wandering around looking at things. “I don’t have any money,” I said.

Mrs. Harper nodded. “Well, how about this then? Why don’t you come be our helper? You can help Mr. Harper and me watch the tables and count money, and then you can pick out one thing to keep, anything you want.”<

br />

I thought about it. If I went over there, she was going to hug me for sure. But there might be some good loot on those tables. Like one of those mats with the bumps to make sure you didn’t slip in the shower. I’d been telling Mom and Dad we needed one, but they weren’t listening. “Anything?”

“Anything.”

“All right, I guess.”

Sure enough, as soon as I walked around to Mrs. Harper’s yard, she gave me a hug, a fourteen-year-long one. When she was finally done with all the hugging, she set me up at a table full of chipped plates and cups and a stuffed dead badger that she said was from when Mr. Harper was in his taxidermy phase. I knew it was a badger because its feet were glued to a piece of wood that said badger on it. She gave me a shoe box to put money in and gave me one last hug-squeeze and left. There wasn’t anything I wanted at that table, but I thought I saw a stethoscope a couple tables over. It was either that or headphones. I’d have to check later.

It wasn’t three seconds before stupid Doug Zimmerman from down the street spotted me and zoomed his way over to my table. He had a forest green bandanna wrapped around his forehead.

“Hello, Aaaaaannie,” he said. He held the “An” part out really long, to be annoying I guess. “What are you doing?”

I straightened out the stuff on the table—a waffle iron, an old pair of dolphin socks, a suitcase with a typewriter inside it—and didn’t even look at him. “I’m helping Mrs. Harper. What’s it look like?”

He shrugged and picked up the waffle iron. “You going to the Fourth of July picnic this year?” he asked, opening up the waffle iron and closing it again. “We could make an obstacle course.”

Far Away

Far Away The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower

The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower The Great Treehouse War

The Great Treehouse War A Tangle of Knots

A Tangle of Knots Sophie Simon Solves Them All

Sophie Simon Solves Them All A Clatter of Jars

A Clatter of Jars Double Dog Dare

Double Dog Dare Umbrella Summer

Umbrella Summer Absolutely Almost

Absolutely Almost Lost in the Sun

Lost in the Sun