- Home

- Lisa Graff

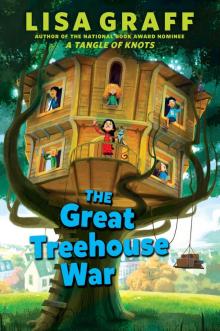

The Great Treehouse War

The Great Treehouse War Read online

PHILOMEL BOOKS

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Copyright © 2017 by Lisa Graff.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Philomel Books is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

Ebook ISBN 9780698195936

Edited by Jill Santopolo.

Design by Jennifer Chung.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Title Page

Also by Lisa Graff

Copyright

Dedication

Your Class Writes!

“Treehouse 10” End Two-Week Siege

Part I: How It All Started The Last Day of Fourth Grade

A Nothing-Special Wednesday

Grim Grades

Artist Vision

Plenty of Peaches

Winnie’s Sunflower Thought

Part II: How It All Happened Talking Through the Window

A Stupendous Slumber Party

A Stack of Surprises

Slumber-Party Fatigue

The Worst Night

The Great Escape

Part III: How It All Ended Advice and Toaster Waffles

Winnie’s Return

Doodles in the Treehouse

An Artist with a Plan

Another Regular Wednesday

The Most Remarkable Thing

A Big Win

“Treehouse 10” End Two-Week Siege

Wednesday, May 3rd

BY MARGARET WEINSNOGGLE

GLENBROOK—Parents around the world breathed sighs of relief this morning, as the second to last of the so-called Treehouse 10—all fifth-graders from local Tulip Street Elementary School—ended their 19-day standoff. Cheers could be heard from blocks away when the ninth child climbed down from the treehouse between the properties of Dr. Alexis Maraj and Dr. Varun Malladi, running to hug his tearful parents. Everyone seemed relieved that the disagreement had at last come to a peaceful end.

Only one member of the Treehouse Ten still refuses to return to American soil. As of press time, Winifred Malladi-Maraj, the treehouse’s original resident, remains inside, with no sign of when she might leave. Neither of Winifred’s parents chose to comment.

Part I

How It All Started

TULIP STREET ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Where every child gets to bloom

360 South Tulip Street, Glenbrook, Pennsylvania 19066

A Note from Mr. Benetto

Fifth Grade Teacher, Room 5L

September 29th

Dr. Alexis Maraj

Dr. Varun Malladi

1 Circle Road

2 Circle Road

Glenbrook, PA 19066

Glenbrook, PA 19066

Dear Dr. Maraj and Dr. Malladi,

I’m writing in regards to your daughter, Winifred Malladi-Maraj. As I mentioned to each of you in our separate parent-teacher conferences after the first week of school, Winnie is smart, curious, and charming, and gets along well with the other students. Most days, however, Winnie is somewhat quiet. At first I believed this to simply be her nature. In my many years as a teacher, I have known many quiet students. And then I noticed something peculiar.

The minute Winnie walked through the door to Room 5L on the first Thursday of school, her face was brighter. All day she was more talkative, more eager to engage. It was as though someone had flipped a switch and brought this previously shy girl to radiant life. I thought that perhaps something amazing had happened the evening before to make her so cheerful. The next day, Winnie was back to her quiet self, and I thought no more of the situation . . . until the following Thursday, when Winnie was once again as carefree as ever. Something, clearly, had happened the evening before—something absolutely wonderful. The following day, the switch flipped back, and once again she withdrew.

I must admit that this morning, on our third Thursday together, I sat at my desk waiting to see which Winnie would walk through the door. And I am both delighted and puzzled to report that it was the happy Winnie—the girl full of sunshine. It’s not bad, this weekly change in Winnie, but it is rather curious, and I was hoping the two of you might be able to shed some light on the situation. If there is indeed something on that occurs each Wednesday to make Winnie so delighted, perhaps it might be possible to bring whatever this thing is into her life every day.

I suppose my question to the both of you, then (and I don’t mean to pry—understand I simply ask in the best interest of your daughter), is this:

What happens to Winnie on Wednesdays?

Yours sincerely,

Hector Benetto

The Last Day of Fourth Grade

a year before what happened happened

There are a lot of things you should probably know to understand why a bunch of kids decided to climb up a treehouse and not come down. But to really understand it, you’d have to go way back in time, and peek through the living room window of a girl named Winifred Malladi-Maraj, on her last day of fourth grade. Since time travel isn’t possible, you’ll just have to picture things. So picture this:

After walking home from school, Winnie stepped through the front door, with her backpack over her shoulder. Winnie’s parents were sitting on the living room couch, with their hands in their laps. They were watching the front door, like they’d been waiting for their daughter for a long time.

Winnie pulled off her backpack and dropped it in the doorway. Buttons, who is the world’s greatest cat, wove his way between Winnie’s legs, like he knew she was about to need snuggling. “Mom?” Winnie said, squinting her eyes at her parents on the couch. “Dad?” She could tell right away that something weird was going on.

It’s probably important to know that Winnie’s parents have never been exactly normal. Like, instead of playing board games after dinner, the way some families did, Winnie’s dad—a biologist—might sit her down for a slide show about his latest research on the beneficial properties of bat guano, which only made Winnie wish she’d never eaten dinner at all. Or Winnie’s mom—a mathematician—might try to explain her current work on the Conway’s thrackle conjecture, which only made Winnie wish she’d never grown ears.

(Once, Winnie made the mistake of asking if she and her parents could play Boggle after dinner, and afterward she’d had to sit through a two-hour presentation of all of her parents’ many awards and grants—none of which, they informed Winnie, had been won playing Boggle—and a four-hour argument about whether or not Winnie’s dad had more awards than Winnie’s mom because there were simply more prizes for biologists than there were for mathematicians.)

> (Winnie never asked about Boggle again.)

But finding her parents waiting for her on the couch together seemed especially weird to Winnie. Because, normally, Winnie’s parents weren’t even home when she got out of school. Normally, Winnie started her homework all by herself and then heated water on the stove exactly at 5:55 p.m., so the pot would be boiling and ready to put pasta in as soon as they got home. (Winnie’s parents were very precise about mealtimes.)

(They were very precise about a lot of stuff.)

Another weird thing Winnie noticed that afternoon was the way her parents were sitting. While she was standing in the doorway with Buttons weaving between her legs, she realized that she hadn’t ever seen both of her parents on the same couch before. When they watched television or sat with guests, Winnie’s mom usually squished herself against one couch arm, while her dad sat in the recliner on the far side of the room.

“What’s going on?” Winnie asked. Even Buttons let out a confused mew?

“Come sit down,” Winnie’s mom replied, patting the couch cushion between herself and Winnie’s dad.

“Yes,” Winnie’s dad agreed. (That was another weird thing, Winnie noticed. Her parents never agreed.) “Have a seat. We marked a spot for you.”

And that was the weirdest thing of all. There was a tiny X of masking tape stuck to the center of the middle couch cushion. Her parents, Winnie realized as she stepped closer, had measured out a spot for her, so that she’d be sitting exactly evenly between them—not one millimeter closer to one than the other.

But Winnie, who was pretty used to her parents being weird, decided there was nothing to do but sit. Buttons sat, too, hopping right into her lap.

“Winifred,” her mom said. She cleared her throat. “Your father and I—”

“Oh no,” Winnie’s dad cut in, putting up a hand to stop Winnie’s mom. “We agreed I would tell her. You got to tell Winifred about the tooth fairy.”

Winnie’s mom frowned. “I don’t see how that’s pertinent, Varun. This is an entirely different—”

“We discussed this,” Winnie’s dad argued. “But once again, you’re attempting to ruin—”

While Winnie’s parents argued, Buttons purred a little louder in Winnie’s lap, scrunching his head under her hand. Winnie scratched and scratched at Buttons’s soft orange fur, while her parents argued and argued. Winnie watched her mom, so angry with her dad. She watched her dad, so furious with her mom. Her parents might have been acting weird, Winnie realized, but the fighting, that was completely normal.

And when she realized that, Winnie knew, deep in her gut, precisely why her parents had sat her down on that tiny X of masking tape.

“You guys are getting a divorce, aren’t you?” she asked them.

Her parents stopped fighting at once. They turned, both together, and they stared at her.

“That’s the thing you were going to tell me, right?” Winnie said.

“Yes,” Winnie’s mom said, putting a hand on Winnie’s knee. “But don’t worry. We have a very sensible plan for how to divide your time equally between the two of us.”

Winnie’s dad put a hand on Winnie’s other knee. “Exactly evenly,” he told her.

For the next half an hour, Winnie sat precisely between her two parents, with one of their hands on each of her knees, as they explained their very sensible plan for her future.

They’d found an unusual street, they told Winnie, a “real gold mine,” called Circle Road, just one block over from Winnie’s uncle Huck’s house.

Winnie scratched a little harder at Buttons’s neck.

Circle Road, Winnie’s parents explained, looped around on itself in a tiny circle, so that there was just enough space for two houses.

Winnie stroked Buttons’s soft belly.

Winnie’s mom would live in the two-story Colonial on the northernmost end of the circle, and Winnie would stay with her on Sundays, Tuesdays, and Fridays.

Winnie caressed the base of Buttons’s ears, just the way he liked.

Her dad would live on the southernmost side of the street, in the yellow split-level (which might have seemed smaller than Winnie’s mom’s house, he informed his daughter, but was technically bigger, because of the square footage of the basement). Winnie would stay with him on Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

Winnie rubbed under Buttons’s orange chin.

Both houses had sprawling backyards, they went on, which backed up onto each other.

Winnie nestled her cheek in the soft fur at the base of Buttons’s neck.

And at the exact center of Circle Road, her parents said, smack in between the two houses—and definitely not (they’d checked) on either parent’s property—was an enormous linden tree, with thick branches that reached in all directions. That’s where Winnie would stay on Wednesdays.

Winnie must’ve squeezed Buttons a little too tightly then, because he let out an angry mew!

“I’m going to live in a tree?” Winnie asked her parents. It was the first thing she’d said in thirty minutes.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” her mom said.

“You’ll be in a treehouse,” her dad clarified. “Your uncle Huck has already agreed to design it.”

Hearing that made Winnie and Buttons feel a little bit better, because Uncle Huck was both an amazing uncle and a fabulous architect. (He was also the one who’d taught Winnie all about Artist Vision, which was something that would definitely come in handy later.) But still . . .

“You really want me to live in a treehouse every Wednesday?” Winnie asked, glancing from her mom to her dad and back again. “All by myself?”

“It’s the only way to split things evenly,” her dad replied. “Since every week has seven days in it. Seven, you know, is not an even number.”

“Yes,” Winnie’s mom said. “We went over and over it. That’s the only way it works. Three days with your father, three days with me, and one day on your own. Doesn’t that sound like a very sensible plan?”

“Um . . . ,” Winnie began, glancing from her dad to her mom and back again. Buttons wasn’t quite sure how he felt about things, either. “I guess?” she said at last.

“I knew you’d think so,” her dad said with a smile. “It was my idea, after all.”

“Your idea?” Winnie’s mom cried. “I very much disagree with that statement, Varun.”

“Oh, do you?” Winnie’s dad said. “What a shock, Alexis, that you feel the need to disagree with me.”

“I’ll disagree with you when you take claim to my proposals, Varun.”

As her parents continued their argument, Winnie scooped up Buttons and headed down the hallway to her room. Neither of her parents seemed to notice that she’d left. Winnie shut the door on their bickering, thinking that perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad after all, having one day a week to herself.

Visit http://bit.ly/2hEskIz for a larger version of this image.

Visit http://bit.ly/2gYxeMO for a larger version of this image.

A Nothing-Special Wednesday

2 days before what happened happened

The Wednesday before what happened happened—April 12th, to be exact—Winnie had no idea that it was any special day at all. Maybe, if she’d known, she would’ve done things differently. Maybe, after school, she would’ve raced to her treehouse even quicker than normal, in eight minutes instead of nine. But since there was no way for her to know what was going to happen, she acted like it was just any other, nothing-special Wednesday.

When she reached the linden tree between her parents’ two yards, Winnie grabbed hold of the rope ladder that clung to the trunk and stuck one foot on the bottom rung. Then she hoisted herself up, quick as a monkey. The treehouse stood about fifteen feet off the ground, so it was a long rope-trek, but Winnie had been climbing it every Wednesday for nearly a year, s

o she was good at it. Just before she reached the bottom of the treehouse, where the under-porch scooped out a little hollow for sitting and unlatching the trapdoor, Winnie reached out her left hand to rub the bronze plaque that had been hammered into the tree’s trunk long, long ago.

That’s what the plaque said. Winnie had looked it up once, and it turned out that the Republic of Fittizio was a former country in Western Europe, which had gone belly-up over a hundred years before Winnie was even born. Winnie had no idea why someone from a now-extinct country would’ve planted a tree in her hometown, far away in suburban Philadelphia, but having the plaque there made her tree feel even more special, so she always gave it a little rub when she climbed past, for good luck.

Winnie spun the combination on the trapdoor’s padlock and pushed her way inside the treehouse. Buttons was sitting in the middle of the treehouse floor, licking one paw and waiting for her. Just like Winnie, Buttons moved from house to house every day of the week—Sundays, Tuesdays, and Fridays at Winnie’s mom’s, and Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at Winnie’s dad’s. On Wednesdays he climbed the branches of the linden tree and squeezed through a cat door just beyond the human entrance, keeping guard till Winnie joined him.

The first thing Winnie did when she got inside (since she still thought it was a nothing-special Wednesday, same as every week), was cross to the kitchen area and grab a snack. The treehouse was pretty big—maybe six and a half kid-lengths wide. The thick trunk of the linden tree ran through the center of the house, all the way up to the second floor, and out the top of the roof, and it was an excellent spot to tack up doodles and drawings. Those weren’t the only decorations in the treehouse, though. When she’d first moved in, Uncle Huck had helped Winnie paint each wall different colors—turquoise blue with white polka dots, pink with wiggly green stripes—whatever she’d felt like. No matter what the weather was outside, the inside of the treehouse was always bright and cheerful.

Far Away

Far Away The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower

The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower The Great Treehouse War

The Great Treehouse War A Tangle of Knots

A Tangle of Knots Sophie Simon Solves Them All

Sophie Simon Solves Them All A Clatter of Jars

A Clatter of Jars Double Dog Dare

Double Dog Dare Umbrella Summer

Umbrella Summer Absolutely Almost

Absolutely Almost Lost in the Sun

Lost in the Sun