- Home

- Lisa Graff

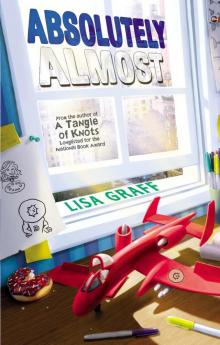

Absolutely Almost

Absolutely Almost Read online

Also by Lisa Graff:

A Tangle of Knots

Double Dog Dare

Sophie Simon Solves Them All

Umbrella Summer

The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower

The Thing About Georgie

PHILOMEL BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Lisa Graff.

Comic book illustrations copyright © 2014 by Richard Amari.

Donut and cup illustration copyright © 2014 by Amy Wu.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Graff, Lisa.

Absolutely almost / Lisa Graff. pages cm

Summary: Ten-year-old Albie has never been the smartest, tallest, best at gym, greatest artist, or most musical in his class, as his parents keep reminding him, but new nanny Calista helps him uncover his strengths and take pride in himself.

[1. Self-esteem—Fiction. 2. Ability—Fiction. 3. Babysitters—Fiction. 4. Family life—New York (State)—New York—Fiction. 5. Schools—Fiction. 6. Racially mixed people—Fiction. 7. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.G751577Abs 2014 [Fic]—dc23 2013023620

ISBN 978-0-698-15853-5

Version_1

Contents

Also by Lisa Graff

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

rocks.

being friendly.

letters from school.

calista.

lights. camera.

a perfect summer day.

noticing.

lunch.

stutter.

einstein.

almost, albie.

a real a-10 thunderbolt.

math club.

an empty tin can.

jokes.

ten words.

some bug.

erlan’s birthday.

reading log.

east 59th street tv.

tuesday.

caring & thoughtful & good.

johnny treeface.

being where you’ve been.

stacking cups.

(not) johnny treeface.

only a test.

patience.

friday.

the zombie in the bathtub.

a fresh piece of paper.

the thing about the cups.

change of plans.

gus.

parent-teacher conferences.

studying.

what’s wrong with my brain.

things i don’t know.

donut days.

afterward.

monday.

six words.

crying.

superheroes.

just like me.

thursday.

friends.

isn’t.

being cool.

still.

tetherball.

helpful hints.

second best.

a note in my desk.

meet the kasteevs.

donut cereal.

nobody.

not funny.

words.

no more helping.

the worst thing ever.

one vote.

thoughts.

vulcan salute.

birthday cupcakes.

something you’ll really love.

flying.

changing channels.

sad.

the surprise in the fridge.

rain in new york.

putting it together.

smart.

one word.

getting where you’re going.

what i could have said.

one last hint.

a note from home.

hannah schaffhauser.

worrying.

the worst worst thing.

voice mail.

mad.

new kid.

what got into me.

lucky.

being famous.

a green pencil.

studying with betsy.

a famous schaffhauser grilled cheese.

new lunch.

wednesday.

gummy bears.

smoothing out the edges.

superpowers.

almost.

things i know.

Special excerpt from A Tangle of Knots

To Jill.

(Absolutely.)

rocks.

Not everybody can be the rock at the top of the rock pile.” That’s what my Grandpa Park said to my mom once when they thought I was asleep, or just not listening, I don’t know. But my ears work fine. “There have to be some rocks at the bottom, to support those at the top.”

I sat in my bedroom, knocking the army men one by one off my windowsill. Dad said I was getting too old to play with them, so I didn’t play, just knocked them over. Plunk, plunk, plunk, on the bedspread. But I did it quiet so no one would hear. plunk . . . plunk. For some reason, I felt heavy inside, listening to them talk out in the living room. Or maybe heavy on the outside, like something was pressing down on top of me, when really it was nothing but air. plunk. plunk.

If I listened real close, I could hear Grandpa Park’s ice clicking in his glass when he lifted it to drink.

plunk.

It was quiet in the living room, no talking, only ice, for a long time. When I got to the last army man, I didn’t set them up again right away. I stared at them on the bed, knocked over sideways or on their bellies. On some you could see the black marker where I’d marked their feet when I first learned to write my name. A for Albie.

It was quiet so long that I thought my mom must’ve gone to bed, and it was just Grandpa Park out there with his glass, drinking down till the ice melted like he usually did when he came to visit. But then Mom said something, so I knew she hadn’t gone to bed after all. She said it real quiet, but I heard.

“Albie’s not a rock,” she said.

being friendly.

Tuesday evening was Chinese from the place on 61st Street, just like every Tuesday. When Bernard rang up from downstairs to let us know the delivery man was in the elevator, Mom gave me two twenties from her purse.

“Wait until he rings the buzzer, Albie,” Mom told me. “And don’t tip more than five.”

“Okay,” I told her, just as the bell rang.

It was my favorite delivery man, Wei. He always smiled big when he saw me.

“Albie!” he shouted, like he was surprised to see me there, even though I answered the door every time. He lifted one of the food bags, like he was waving.

“Hi, Wei,” I said, smiling back. “How much?”

“Twenty-seven sixty.” He showed me the receipt stapled to one of the bags, be

cause sometimes with numbers it was hard to understand what Wei was saying.

I took the bags and handed them to my mom, who put them on the table. They smelled greasy and meaty and delicious, like Tuesday evening. “Thanks,” I told Wei, handing over the two twenties. “Can I get . . .” In my head I rounded up the change, like Mom and Dad do when they give tips in the cab. “Four dollars back?”

“Sure thing.” Wei took a wad of bills out of his pocket and placed the twenties on the outside, then flicked past the tens and fives till he got to the ones, in the middle. He peeled off four for me.

“Here you go, Albie.” Wei handed over the bills. “Shee-shee.” At least that’s what it sounded like he said.

I raised an eyebrow at him.

“Thank you,” he explained. “How do you say ‘thank you’ in Korean?”

I looked at Mom. Sometimes people think I know Korean, because I’m half, but I only know “hello” and a couple foods. Mom spoke it with her grandparents, but I don’t think she likes to anymore.

Mom was busy setting the food out on plates, so she couldn’t tell me how to say “thank you” to Wei in Korean.

“I’ll tell you next time,” I said.

He winked. “Bye, then!” he said.

“Shee-shee!” I answered, and I closed the door.

Dad snapped shut his laptop and got up from the couch as I handed Mom the change.

“Oh, Albie,” Mom said, looking at the four dollars. “I said don’t tip more than five.”

I didn’t, I started to say. I just rounded up the change. But before I could tell her that, Dad put a hand on my shoulder. “He was just being friendly. Weren’t you, Albie?” He looked at Mom, still staring at the four ones. “It’s just a few dollars.”

That’s when I started to get the feeling in my brain I sometimes got, when something that was clear before all of a sudden turned fuzzy. I sat down and Mom scooped some rice onto my plate, with kung pao and an egg roll.

Twenty-seven sixty. I put the number in my brain and tried to keep it there while I chewed my egg roll. Twenty-seven sixty. I’d started with forty dollars, and I gave Mom four. Over and over I tried to subtract the numbers, but I didn’t want to do it on paper because I didn’t want Mom and Dad to know I was subtracting, so it was hard. Every time I did it, I got a different number.

Fuzzy.

Fuzzier.

I gulped down the last of my egg roll.

“Everything okay, Albie?” Dad said, looking at me carefully.

“Yep,” I told him. I picked up my fork and mixed the kung pao up with my rice, and decided that maybe I was being friendly after all.

letters

from school.

E-mails from school are never about good stuff. The teacher never writes to your parents to say things like “Albie’s so wonderful to have in class! Just wanted to let you know!”

Or

“Albie always lets Rick Darby borrow his pencils, even though Rick barely ever gives them back!”

Or

“Today Albie picked Jessa Kwan first for his team in basketball, because Jessa usually gets picked last, and he felt bad!”

(My team lost in basketball that day.)

E-mails from school are always bad, but they try to hide it with big words that are hard to understand.

Potential.

Struggling.

Achievement gap.

Words that make my dad slam his fist on the table and call my teacher to shout about setting up a parent-teacher conference, and my mom to go out and buy fruit. When Mom comes back with strawberries, her face is always crystal clear. Not an almost-crying face at all.

I used to really like strawberries.

E-mails from school are always bad, and they’re always about me. But letters from school—the kind that are written on real paper and sent in a real envelope, with a stamp and everything—those are even worse.

When the last letter came from Mountford Prep, my old school, Dad didn’t yell at my teacher. Mom didn’t go out and buy strawberries. They just sat at the table, blinking at me, their shoulders slumped like when our dog, Biscuit, ran away.

“What does it say?” I asked. It was open, in front of my dad across the table, but I couldn’t see any of the words. Only the big red letters at the top of the page, spelling out the name of the school.

“It doesn’t matter,” Dad said. He looked mad, like his eyes were hurting him. He crunched up the letter and tossed it in the recycling.

“I think a new school will be good for you,” Mom said.

• • •

It’s my job to take the trash to the garbage chute every week, or whenever it’s full. Recycling too. It’s part of my chores. I get five dollars a week allowance.

That day, the letter day, I did my chores. But one tiny piece of recycling never made it down the chute. I smoothed out the letter from Mountford Prep, and folded it back along the creases, and put it in the bottom drawer of my dresser with my swim trunks.

I never read it. I didn’t want to. But I didn’t want to throw it out either. I don’t know why.

Maybe P.S. 183 doesn’t believe in sending home letters.

calista.

Mom waited two weeks for Dad to free up his schedule so he could help her pick the new nanny, but he kept being busy, so finally she picked by herself. The nanny came over on Tuesday to meet me.

“Hey, Albie,” she said from the doorway. She waved one hand. The other was wrapped around a cup of takeout coffee from the bodega downstairs. I knew it was that bodega because I heard the owner, Hugo, say one time that they’re the only ones for fourteen blocks who use the blue cups. “I’m Calista.”

I didn’t want to look up to meet her, but finally I did. It was better than the supplemental reading packets Mom had gotten for me, anyway.

She was short, but not too short for a girl, I guess. She was wearing jeans, even though it was too hot outside for jeans, and sandals, and a pink-and-orange plaid short-sleeve button-down shirt. Her hair was braided in two braids on either side of her head—not the regular kind of braids, but the complicated kind the girls do to each other during assemblies, the kind that start all the way above the ears and take forever. I wondered why she would wear her hair like that, because it made her look like a kid. Maybe that was why.

My mom walked to the kitchen and took a glass out of the cupboard. “Calista, would you like some water?” She started filling it before the new nanny even had a chance to answer. “Albie, don’t be rude,” Mom told me. “Say hello.”

“I’m too old for a nanny,” I said. Which was true, because I was ten.

“Albie!” Mom squawked. The ice tumbled out of the square in the fridge door and into the glass. “He’s not normally like this,” she told the nanny.

“That’s all right,” the girl said. But she didn’t say it to my mom, she said it to me. She sat down in the chair next to me, still holding tight to her coffee, and smiled. “I’m not really a nanny,” she said.

“More like a babysitter,” Mom piped up from the kitchen.

I was too old for a babysitter too.

“We’re just going to hang out together,” the girl told me. “I’ll pick you up from school. Maybe we’ll go to the park a little bit, I’ll help you with your homework.”

“She can help you make flash cards to study,” Mom said as the water poured in around the ice. I scrunched up my nose.

“And when your parents have to work late, we’ll do dinner and play games,” the girl went on. “Do you have Monopoly? I love Monopoly.”

“That sounds like a babysitter,” I told her.

My mom walked over and handed the girl the glass. It had little wet speckles of cold on the outside already. “Albie, you should show Calista your chess set. He has a gorgeous chess set, from Guatemala. Maybe you can practi

ce so you can join the chess club at your new school. What do you think of that, hmm, Albie?”

I squinted at the girl.

“Just hanging out,” she promised. She set the glass on the table, and my mom scooped it up to put a coaster underneath it.

I looked back down at my packet of supplemental materials. “I don’t need to be picked up from school yet,” I said. “There’s still two weeks of summer.”

“We thought Calista could take you to the Met tomorrow,” Mom said. “Albie, you know she’s from California? Just moved to the city two weeks ago. You’ve really never been to the Met before?” she asked the girl.

The girl pushed back the plastic tab on her coffee lid and took a sip. “Maybe you can be my tour guide,” she told me.

I squinted my eyes at her. There was a tiny chunk of hair, woven into the very back of her braid, that was neon pink. It matched the checks in her shirt. I wondered if Mom had seen it. Probably not, or I bet she never would’ve picked her for my nanny. Dad would hate it.

“Okay,” I told Calista.

lights. camera.

Erlan Kasteev has always been my best friend, since six years ago, which was when we met. Lucky for both of us we live in the same building, on the same floor even. My family is 8A, and his is 8F. Which makes it easy to know if he’s home, because I can check for his bedroom light from my kitchen window.

I knocked on Erlan’s door, and one of his sisters answered. Alma, I think. I always had trouble telling his sisters apart, because they were triplets and they looked alike. Not identical—that’s what Erlan told me, although they looked identical enough to me. Alma, Roza, and Ainyr. They were all two years older than Erlan, with dark straight hair and dark eyes. Erlan was a triplet too, but I could always tell Erlan apart from Karim and Erik. Erlan said he and his brothers tricked their teachers all the time, and the other kids at our old school. He said they even tricked his parents once. But not me. I always knew. That’s because Erlan just looked like Erlan.

“Oh,” Alma or whoever said when she saw me at the door. “It’s you.” Then she screamed over her shoulder, “Erlan! Your lame friend is here!”

Far Away

Far Away The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower

The Life and Crimes of Bernetta Wallflower The Great Treehouse War

The Great Treehouse War A Tangle of Knots

A Tangle of Knots Sophie Simon Solves Them All

Sophie Simon Solves Them All A Clatter of Jars

A Clatter of Jars Double Dog Dare

Double Dog Dare Umbrella Summer

Umbrella Summer Absolutely Almost

Absolutely Almost Lost in the Sun

Lost in the Sun